La Campana National Park

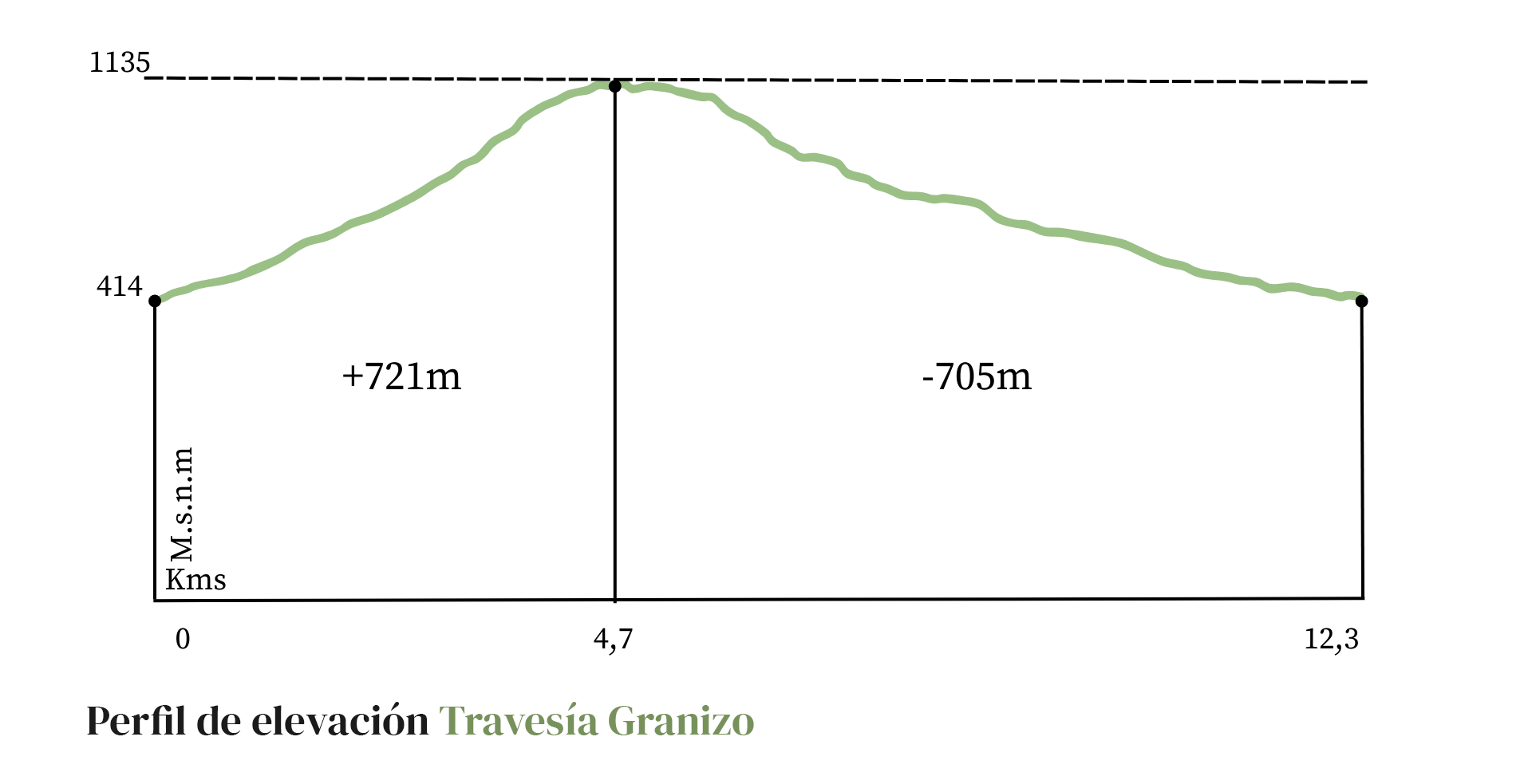

Granizo - Ocoa Crossing

12.7km8hr721mt

Difficulty: Medium - High

A crossing trail that joins two entrances to the National Park, starting at the Granizo de Olmué entrance and ending at the Ocoa entrance. A hike of medium difficulty, although longer in duration and higher in altitude than the previous ones.

A complete sequence of visits to different plant communities in the sclerophyllous, hygrophilous and deciduous forest environments, crossing the northern limit of the Nothofagus genus in South America, with the last oak forests; as well as the thorny scrub environments, where the largest relict population of the Chilean palm, a survivor of the tropical forests that were introduced before the formation of the Andes Mountains, is located.

All of these, filled with echoes and traces of different times that appear during the hike.

It is recommended to go on this hike after the first rain of autumn until before the arrival of the warmth of spring, and not to do it on rainy days, given the fragility of the trails and the increased risk of accidents.

IMPORTANT: It is recommended to plan the time of the hike well, adjusting to the opening and closing times of the National Park. It is suggested to start the activity on time, at the opening time of the accesses, in order to have time for photography and short breaks.

1. The Patagua

Due to the humidity at the bottom of this ravine, which collects water from the mountain range, and the shadows of its south-facing slopes, these ancient pataguas are able to settle here.

The Patagua (Crinodendron patagua) is a species typical of the hygrophilous forest of the Mediterranean climate zone, which is distributed between the Aconcagua River and the Biobío region.

It grows as a shrub or evergreen, woody tree. It reaches up to 10 meters high and settles in environments like this, both in the Coastal Range and in the Andes, reaching heights of up to 1,200 meters above sea level.

2. The Maray

The Maray is an artisanal tool used for centuries since the Inca period for the fracturing and grinding of minerals.

The Incas worked gold washing sites in the Marga Marga valley and at the foot of La Campana hill. From the Qhapaq Ñan, the Andean road system that was the backbone of the political and economic power of the Tawantinsuyo, there was a branch that crossed the La Dormida slope, crossed this valley of the Limache estuary and went up to the top of the Marga Marga basin. Pedro de Valdivia himself, a few months after the beginning of the Spanish conquest, went into these valleys in search of the secret of its location revealed to him by Michimalonco.

Fernando Venegas recalls the words of Benjamín Vicuña Mackenna at the end of the 19th century, when he commented that "the La Campana hill, which gives it shade, horizon and fame, was then surrounded, according to travelers, by the vestiges of gold mills, whose ruins are today everywhere a mysterious statistic... and a comfortable seat for the weary traveler in its huntings and walks".

3. Lichens

La Campana National Park reveals itself as a fascinating natural laboratory for the study of biodiversity, highlighting the presence of lichens as indicator organisms of environmental health. Lichens, formed by symbiosis between fungi and algae or cyanobacteria, play a crucial role in the ecology of the park and offer a unique window to understand the interaction between organisms and their environment.

Lichen Diversity:

Lichen diversity in La Campana National Park is notorious, reflecting a wide range of adaptations to the specific climatic and edaphic conditions of the region. The presence of species such as Cladonia rangiferina and Parmotrema tinctorum reveals the ability of these organisms to colonize diverse habitats, from rocks to tree logs.

Environmental Effects:

The study of lichens in this ecosystem provides valuable information on air quality and the presence of atmospheric pollutants. Given their sensitivity to pollution, lichens can serve as bioindicators, allowing us to evaluate the environmental health of the park and detect possible anthropogenic impacts.

Symbiotic Interactions:

The symbiotic relationship between fungal and photobiont components of lichens is essential for their survival. The specific conditions of La Campana National Park, such as altitude and relative humidity, influence the composition of these symbiotic associations, providing fertile ground for further research into the factors that determine the dynamics of these communities.

Conservation Importance:

The conservation of lichens in La Campana National Park takes on crucial importance in the context of biodiversity preservation. Since these organisms play essential ecological roles, their study and protection contribute directly to the overall health of the ecosystem, promoting the stability and resilience of the surrounding flora and fauna.

4. Lingue and Canelo

In this sector of hygrophilous lauriphyllous forest, two new species of trees stand out, which require special environmental conditions to adapt to these latitudes.

The Lingue (Persea lingue), is endemic to Chile and is distributed between Aconcagua and Chiloé. It is an evergreen tree, reaching up to 25 m in height.

A relative of the avocado tree (Persea americana), it grows vertical when young, slowly widening its crown. Its smooth-edged leaves are elliptical, green above and reddish below. The fruit is a fleshy berry with a bluish-black seed, which especially attracts pigeons.

Its wood is highly valued. And its bark is used as an infusion in natural medicine: it contains tannin, applied in chronic dysentery and in cases of tumors, leucorrhea and chronic metritis.

The canelo (Drimys winteri), sacred tree of the Mapuche people, symbol of benevolence, peace and justice, extends between the region of Coquimbo and Cape Horn.

It is an evergreen tree, with dense foliage and a pyramidal crown. Its leaves are smooth, lustrous green on the top and grayer on the bottom. Its flowers are of regular size, pure white color and reddish petioles, which exhale a soft fragrance and conglomerate in a kind of cluster. Its fruits are blackish oval berries, containing 6 to 8 seeds.

For the machis, its bark and leaves have tonic and stimulating properties, healing pain and diseases. Its decoction was used to give baths to paralytics, in odontological treatments, ulcer and scabies. And on its branches the sick were laid down during steam baths".

It gained curative fame for the treatment of scurvy, a disease that devastated sailors crossing Cape Horn, due to the lack of vitamins. In 1579, John Winter, Sir Francis Drake's vice-admiral, took the bark to Europe after using it to cure the disease among crew members. Hence the scientific name assigned to the species is Drimys winteri.

5. Tayú del norte

We are in a sector where the Tayú del Norte (Dasyphyllum excelsum), also known as palo santo, is most abundant in a very special environment, which is conducive to its survival and settlement in small communities. It is a species declared in extinction danger in the year 2022, endemic of central Chile, perennial, evergreen.

It is currently distributed in a few ravines with relict characteristics between the regions of Valparaíso and Maule, in a fraction of what would have been its original distribution.

It would be a living ancestor, being part of a group of the Asteraceae family, which according to the Argentine botanist Angel Lulio Cabrera, "would have had its origin in the mountains of the Cordillera de la Costa, from where it would have migrated to much of South America before the rise of the Andes".

You can recognize it by taking into account that it is a tree of straight and cylindrical shaft, of soft, grayish bark and marked with deep longitudinal crevices. Its stems are covered with whitish hairs. It has alternate, dark green, ovate leaves. They have thorns at the base of the leaves.

6. Sclerophyllous forest and coastal fog

During the winters, thick morning mists that come from the sea and are driven by the winds, penetrate the Olmué valley, crash against the mountainous system of La Campana and El Roble hills and are used by the sclerophyllous forest to settle.

This same phenomenon is known further north as "camanchaca". It is formed by a layer of stratocumulus-type clouds that persistently cover a coastal strip that runs from Peru to central Chile.

The vegetation is favored by climatic compensation factors such as the influence of these coastal fogs, the low incidence of solar radiation and its location in the windward zone of the Coastal Mountain Range.

We are in the middle of the plant community of the sclerophyllous forest of peumo and boldo, with a strata of evergreen trees, poor in shrubs and a herbaceous strata with some ferns and an abundance of vines.

The Peumo (Cryptocarya alba), is an evergreen tree, endemic to Chile, which grows between the provinces of Limarí in the north to Cautín in the south. It flowers between November and December. You can recognize its yellow flowers or its fleshy, ellipsoid, white or pink fruit.

The Boldo (Peumus Boldus), also an evergreen tree endemic to Chile, grows between the bay of Tongoy and Osorno. It flowers from June to August. Its fleshy, yellowish-green fruit is sweet and aromatic. Its oval and rough leaves are used as an infusion to treat liver problems.

7. Mining

Around 1830, a priest from the Santa Cruz de Limache parish discovered a copper vein in the La Campana hill. His discovery spread throughout the region and soon the hill was covered on all sides, Olmué and Ocoa.

In the middle of the century, mining began on an industrial scale and at the end of the 1920's the Compañía Minera e Industrial La Campana was formed, with 26 mining properties on the hill. This company went into crisis during the Second World War. It was reactivated at the beginning of the 1970s and it was not until 1994 that the last deposits in operation were closed.

The mining activity inherited the roads inside the National Park, which are currently used by park rangers and cyclists. However, it had a strong impact on the landscape. Accumulations of sterile material, forming mounds or cones in the vicinity of the deposits. The mining work modifies the profile of the slope, favoring the gravitational fall of rocky materials, dragged by finer sediments down the hillside during the rainy season.

8. Oaks

The ascent brings us to a new forest community, a deciduous forest - twhich loses its leaves annually - with a predominance of Oak (Nothofagus macrocarpa), an endemic species, which is observed intermittently along the Coastal Range between this area through the north, and to the south of Pichilemu. And along the Andes Mountains, between the latitudes of San Fernando and Talca.

These forest formations are found in high areas, isolated from each other, where the microclimate conditions allow their survival. They are distributed in small sectors, located mainly in places with southern exposure, more humid and cold, avoiding sunlight and high rates of evapotranspiration.

They can only be found at this latitude, thanks to climatic compensation factors associated with coastal and windward fogs, which provide greater humidity to the environment. And the effect of a higher altitude on temperatures, reaching areas where it usually snows.

Its wood was intensely exploited as railroad ties for the construction of the train that linked Santiago and Valparaiso, leaving mostly young forests.

This place is also the northern limit of the Nothofagus genus in South America, which in Chile has 9 other species, characteristic of the temperate forests of the south and Patagonia.

The origin of the genus Nothofagus dates back to 80 million years ago in what is currently the Antarctic Peninsula, still part of the supercontinent of Gondwana, long before it froze. Through land bridges they were able to disperse and populate territories that are currently the southern part of Chile and Argentina, as well as Australia, New Zealand and New Guinea, currently separated by the enormous Pacific Ocean, a product of continental drift.

9. Portezuelo

We reach the summit line, the Portezuelo de Ocoa, the highest point of the journey, with a multiplied panoramic view.

The watershed, delimited by a stone wall in the form of a pirca, which also separates two properties of very different history and characteristics. Towards Granizo de Olmué, it was the Indian heirs of the encomendera Mariana de Osorio in the 17th century who organized themselves as comuneros. Towards Ocoa, an hacienda that belonged to the Jesuits in the 18th century, was after their expulsion, administered as a large estate that was subdivided into 5 parts at the end of the 19th century, one of which is the current Ocoa sector of the National Park.

To the north, we can see the Aconcagua valley and the transversal mountain ranges that accompany its course. On clear days we can see 144 km away the snow-capped peaks of Mount Mercedario, located in the province of San Juan, Argentina, which reaches an altitude of 6,770 meters above sea level.

To the south, the valley of the Limache Stream, whose waters originate in the Dormida canyon, at the foot of the Vizcacha and Punta Imán hills, running almost parallel to the Aconcagua, finally pours its waters into the Aconcagua only 8 km from its mouth.

On a regional scale, we are at a transition point between a Mediterranean-type climate and a semi-arid one. On a local scale, we pass from a shady climate, with a majority of south-facing slopes, to a sunny climate, with noth exposed slopes. The coastal fog loses the influx that we have analyzed so far, when we enter Granizo.

All these factors have important consequences on the diversity and distribution of the plant communities we are visiting. From the predominance of forest areas, we move on to areas with a predominance of sclerophyllous scrub.

Descending along the trail, the presence of the Chagualillo (Puya coerulea) stands out; a plant up to 2.5 meters high, elongated gray leaves, with a thorny margin gathered in inclined rosettes, which grows only in the coastal mountain range between 500 and 2,000 meters above sea level, between the regions of Coquimbo and Valparaiso.

It settles on granitic rocky substrates, facing steep hillsides, and then disappears below 1,000 meters above sea level.

10. El Amasijo Ravine

Pay attention to the ravine you see under your feet. It is called El Amasijo. Its waters supply the Rabuco stream, which is born when it joins the waters coming from the El Cuarzo ravine, to your right, and dies when it pours its waters into the Aconcagua River.

From the summits of this small basin, blocks of rocks have broken off, rolling down the slopes at different angles. Deposited there by some natural accident; then fragmented by the effects of water and temperature changes, until they gradually became maicillo and mixed with mud.

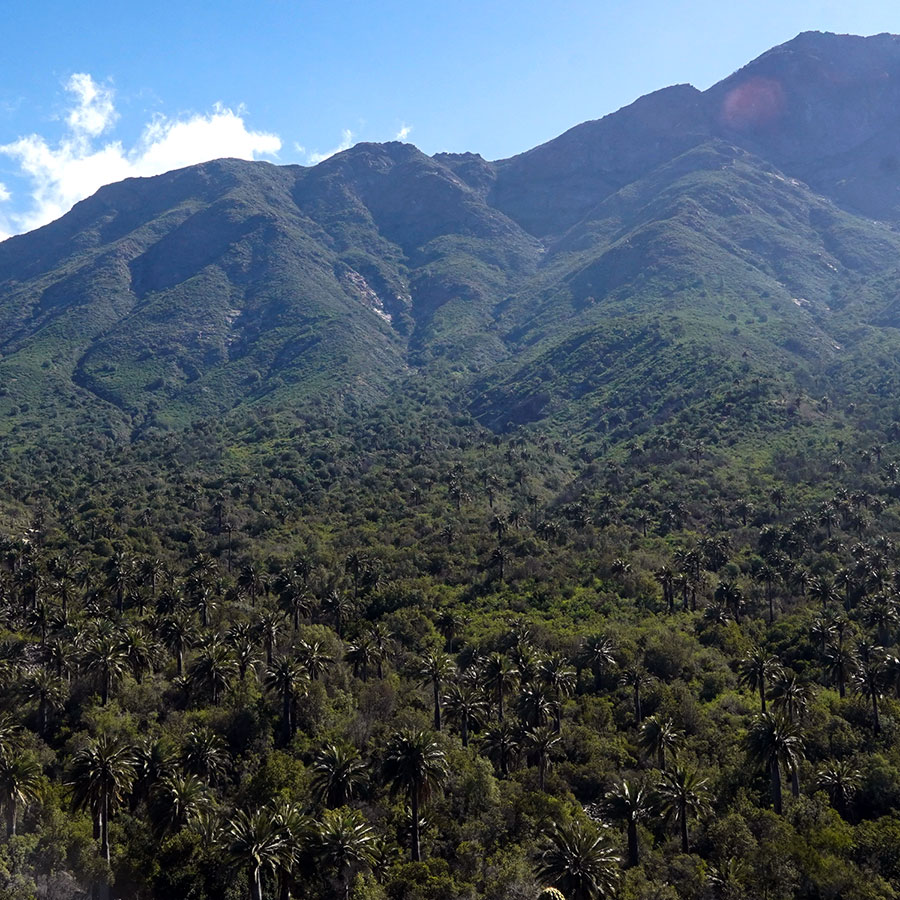

And it is in this special scenario where the largest population of Chilean palms, the southernmost palm species on the planet, endemic to central Chile, is located. It is a true survivor of the tropical forests that existed 30 million years ago in our territory, before the Andes Mountains were formed, which would act in the future as a barrier to species intrusions.

It also survived the subsequent overexploitation it suffered from colonial times until the end of the last century, as a result of the extraction of its sap and the manufacture of a sought-after honey. It is estimated that only 5 percent of its original populations exist today.

A 2017 study, aimed at quantifying the number of specimens in their different geographic distributions in the country, between La Serena in the north and Pencahue in the south, calculated a total population of 121,000 specimens. And almost two thirds of these individuals are concentrated here, in the small Ocoa Valley!

11. Agua El sapo

The watering holes are mandatory resting points for the herders who have historically brought their animals to these hills to graze, following old community traditions.

The country communities, formally called Agricultural Communities since the 60's of the last century, are a particular collective form of land tenure whose origin can be traced back to colonial times, since the sixteenth century, especially in hill areas of low agricultural productivity, which were not of interest to the conquerors.

"In their daily existence the comuneros continue to carry out transhumant cattle raising, even though they lose money. They continue with their landscapes of adoration, brotherhoods of Chinese dances, they light candles to the Virgin and make prayers to the saints and patron saints, so that it rains, so that they have water for the crops, so that there is pasture in the mountain ranges. They continue to recover their local history, recording their past of courage and resilience in the face of adversity".

In favor of the herders, it is thought that their animals have played an important role in colonizing the higher zones with palms, disseminating their coquitos through their feces.

12. El Amasijo

We are in the core area of La Campana National Park, in a zone where the main objective of protection that motivated the creation of the National Park is concentrated: the Chilean Palm.

Researchers from the University of Chile carried out studies of genetic diversity of the species in the different locations where the Chilean palm is found in the country, revealing that there is a high degree of inbreeding among them, which expresses endogamic traits that diminish their capacity to adapt and evolve in the face of environmental changes, leading to a greater risk of extinction.

Crosses are made between plants of the same population or "close relatives" and there is little survival of seedlings in a natural way. On the other hand, natural seed dispersal - another mechanism that promotes gene exchange - is carried out by small rodents such as the Degú (Octodon degus) and the Cururo (Spalacopus cyanus), animals that feed on these seeds and move them from one place to another, but they do so at distances of no more than six meters, unlike in the past, when this process was carried out by larger species, such as the extinct megafauna or the guanaco, which moved these fruits over greater distances.

The causes of this low genetic diversity include habitat fragmentation, the deterioration of the Mediterranean forest, human activities, the lack of animals that disperse their seeds over long distances and the deficit of natural regeneration.

13. Trail erosion

Trails deteriorate over time and need to be maintained so that people can walk on them in a sustainable and safe way.

Their deterioration is influenced by erosion caused mainly by rainfall on the path surfaces. This can be due to steep slopes, poor drainage gradients or unstable soils.

The historical use of the track also has an influence. The herder’s tracks tend to generate deep potholes such as the ones we have been passing through in the last few routes. The horse's foot is smaller than ours and the pressure exerted by its footprint is several times greater. And when the ground is muddy, it digs deeper.

This route passes through different types of paths, some more demanding than others, changing from forest to scrubland, alternating between valleys and mountains, dazzling us with the distribution of rocks and palm trees. It also makes use of small stretches of roads built by the old mining entrepreneurs who once operated in what is now La Campana National Park.

Since walking gives us pleasure, we should also be concerned about the condition of the trails, whether they are well signposted and whether we cause as little damage as possible with our footsteps, both on the road and in the surrounding area.

What better place to make this reflection, where the palm tree and path simulate a fight between titans. A silent call to the responsibility of the hiker to protect the trail and this lonely individual.