La Campana National Park

El Quillay Circuit

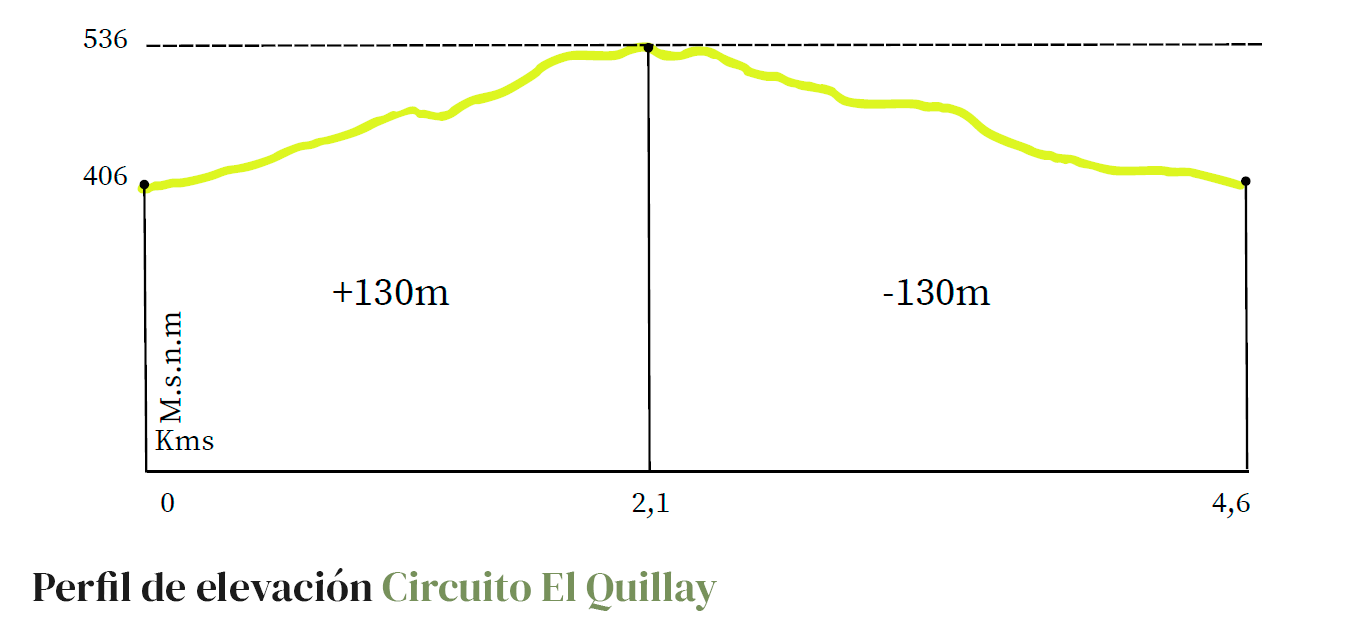

4.6km2hr 18min130mt

Difficulty: Low

A low-difficulty tour, through areas of ravines and low hills, with an abundance of Chilean palm , alternating between sclerophyllous forest, hygrophilous forest and thorny scrub.

All this, splashed with echoes of different pasts that appear during the walk, through their traces.

It is recommended to visit after the first rain of autumn until October, to avoid intense heat and sun exposure.

Drag

1. Watershed - Divisoria de Aguas

The ridgelines we can observe correspond to watersheds between different hydrographic basins. The visible part corresponds to the Ocoa basin, which flows into the Aconcagua River.

And the invisible part? The line segment to your right that culminates at the summit of La Campana hill, separates the waters of El Bellotal de Rabuco ravine, which also flows into the Aconcagua. Behind the segment that continues to the left of this peak up to Punta Imán, it flows into the Limache stream, whose waters also feed the Aconcagua River just 8 km from its mouth in the Pacific Ocean.

Between Punta Imán and El Roble hill, we separate from the mini-basin of the Caleu stream, whose waters flow first into the Til Til stream and then successively into the Lampa and Colina streams, and from there into the Mapocho and Maipo rivers until culminating in the sea, on the border of the municipalities of San Antonio and Santo Domingo.

After the line that continues to the left of El Roble hill, its waters also flow into streams that are tributaries of the Aconcagua river.

2. Lonely Palm

The Chilean Wine Palm or Jubaea chilensis is a species native to Central Chile and although it has a wide geographic distribution, ranging between the Coquimbo and Maule regions, its populations are fragmented and currently found in a few specific sites.

Since the Chilean palm population in the national territory has decreased by about 98% in the last two centuries and the rate of young specimens is very low, this species has been categorized as vulnerable.

The regeneration of palm groves is a multi-stage process since, like other plants, their flowers must be pollinated to produce fruit whose seeds must then be dispersed. Afterwards, the seeds must find the appropriate soil, temperature and humidity conditions in order to germinate. But the process does not end there, as the seedlings must be able to survive the early stages of their development in order to reach the dimensions of the palms we see in the park today.

The palm seeds, small coconuts which are highly sought after by rodent species such as the Degú (Octodon degus), are harvested for human consumption because they taste very similar to tropical coconut. Honey is also produced from the extraction of its sap, and although this is currently carried out through a sustainable process that does not harm the palm, in the past they were extracted to be drained.

When these practices are carried out indiscriminately and the normal development of the palm is altered, it interferes with its reproduction and regeneration cycle. If the soil conditions surrounding a specimen are also affected, there will be cases of isolated species. The large solitary palm is at least accompanied by trees of the sclerophyllous forest such as the Maitén (Maytenus boaria) and the Quillay (Quillaja saponaria).

3. Ecological succession

Changes in weather conditions and land use favor the colonization of new species and the extinction of others, which leave visible traces in time and space.

It is not uncommon that in long periods of drought, forest areas gradually give way to thorn scrub and xerophyte species, which, thanks to the modification of their leaves, stems and roots, are able to absorb and retain water for long periods of time in order to survive.

As you can see, nothing is static in nature. Ecosystems become more or less complex, depending on the diversity of living beings they contain and attract.

4. La Buitrera Camping

La Buitrera is the name of this beautiful ravine and the nearby cliff areas, where large birds of prey such as the red-headed vulture, nest and take shelter.

This campsite was set up to welcome visitors to the National Park, combining shaded areas in the middle of this beautiful forest of sclerophyllous species and Chilean palms, with other sites without shade, designed for the coldest days or to enjoy the starry nights.

It unfortunately had to be closed years ago, due to the prolonged drought and the lack of water available to accommodate visitors, and today it is only used as a picnic area.

A trace of the recent history of the Park and a humanized evidence of the socio-ecological successions.

5. Changes in Environmental Conditions

As observed at different sites along this route, ecological succession takes place where species are replaced by others with better adaptive skills to the changing environmental conditions.

Within the types of succession, primary succession can be distinguished. It occurs in places where there is no vegetation, therefore the seeds of plant species from other sites colonize the soil, creating the conditions for the arrival of other species.

On the other hand, in the national park, secondary succession occurs in places where a certain vegetation formation already exists, and is gradually replaced by new species.

A good example of this is shown in this area, where some Peumo trees (Cryptocarya alba) that have reached a great height have generated the conditions of shade and humidity necessary for the proliferation of Quillay tree (Quillaja saponaria) seeds, a species better adapted to resist the decrease in precipitation and the increase in temperatures, typical consequences of climate change.

Disturbances such as wildfires, excessive logging, animal overgrazing and the extraction of leaf soil, also trigger these processes of ecological succession.

It is important to note that the extraction of leaf soil for gardens, carried out for centuries, considerably reduced the quality of the soil where the sclerophyllous forest is located; since, by removing organic matter, the availability of the nutrients that sustain it is reduced.

6. Fruticose Lichens

A lichen may look like a single organism, but it is actually a complex entity made up of several organisms living in symbiosis, formed by a fungus, which is the main element, along with a green algae and/or a cyanobacterium.

They are essentially collaborative, not competitive, neither dominating the other. The alga or cyanobacterium takes care of the food and the fungus provides a home. While the fungus is not able to carry out photosynthesis, the algae component does, providing the nutrients - mainly carbon nitrates and nitrogen compounds - so that the fungus can develop the secondary metabolite. For its part, the fungus is able to adhere to its support and offer protection to the algae component, in addition to providing salts and mineral waters obtained from the substrate.

They are able to colonize almost all known ecosystems and can survive extreme weather conditions. However, their weakness is being very sensitive to pollutants such as sulfur dioxide and ammonia. They are an interesting bioindicator of the environmental conditions of a specific place, acting as a natural indicator of pollution. A higher concentration of lichens is directly related to cleaner air and water.

Lichens can acquire different forms depending on the substrate to which they are attached. On rocks, crustaceous forms predominate, with radial growth, and their bodies are completely attached to the rock. On the bark and branches of trees they present fruticose forms, like those that proliferate on the trunks and branches of the Litre (Lithraea caustica) and Espino (Vachellia caven) trees that surround you. Their bodies are elongated, resembling a mane, attached to the substrate by a single point while the rest of the organism is far from it, and can branch profusely. Finally, they adopt foliose forms, in which their bodies are partially detached.

7. The Hygrophilous Forest

As you descend to the bottom of the ravine, you will feel the humidity of an environment favorable for the settlement of previously unseen species of trees such as:

The Patagua (Crinodendron patagua)

It is a fast-growing evergreen woody tree, endemic to Chile, whose bark contains tannin, a substance used for tanning leather. Its leaves are simple, elongated and have a saw-like edge. Its beautiful flowers are white, and have five petals, with honey-generating importance. Its fruit takes the form of a dry capsule, which, when ripe in late autumn, opens to release its seeds, which germinate at the end of winter.

The Canelo (Drimys winteri)

Sacred tree of the Mapuche people, it is an evergreen tree that lives only in Chile, between the Coquimbo region and Cape Horn, as well as in western Argentina. John Winter took samples of this plant to England, considering it very useful to combat scurvy, a disease that devastated the crews who crossed the Strait of Magellan in the era of exploration. His surname became associated with the scientific name of the plant.

8. Forces of Nature

We are located at the bottom of La Buitrera creek, a secondary water collector that supplies the Rabuco stream, the main effluent of the Ocoa basin.

Its drainage pattern is formed by primary and secondary tributaries, which join freely in any direction, having the shape of an extended hand where each tributary of the main river is equivalent to each finger of the hands.

You may have noticed that the slopes of the hills that surround us present drainage forms, which are characteristic of massive igneous rocks without structural control. They are rocks formed by the solidification of magma; through a very slow crystallization process, which resulted from the cooling of minerals and the interlocking of their particles.

These fragmented rocks that roll at a slow pace in the direction of the ravine axes, are dragged in days of intense rain and landslides, and are subjected to continuous weathering during their long periods of settlement in each place.

The stone boulders are characteristic of the polishing of coarser rocky materials generated by surface water erosion.

Their finer particles became detached from the layer of gravel covering them.

9. Tevo Bush

In the Mediterranean climate zone of central Chile, it is very characteristic to find a predominant thorny scrub plant community on the slopes exposed to the north, like the one we will now visit. Typical of arid environments, its hard and sharp thorns are the result of the transformation of its leaves, which has allowed the plant to save water for its sustenance.

We enter a bush community where the Tevo scrub appears (Retanilla trinervia or Trevoa trinervis), a species present between the regions of Coquimbo and Maule, here accompanied by low forms of Litre (Lithraea caustica) and Quillay (Quillaja saponaria or Soapbark).

The Tevo is a bush with branches containing horizontal thorns in pairs, used to defend itself from predators. It has three-veined leaves and yellowish spring flowers, which bear a drupe-like fruit, hairy and ovoid. Its flower is very aromatic and has been used in the production of perfumes.

Since ancient times, the epidermis of its bark has been used to treat bruises and small superficial wounds, applied as an ointment to the affected area. It is said that it was widely used by the Picunches to heal their wounds after their battles against the European invaders.

10. A Singular Rock

We can observe this rock covered by crustacean-shaped lichens. It settles on some of the rock’s faces and not on others, taking advantage of special conditions of exposure to the sun, as well as the roughness and porosity of its surface.

On the other hand, you will be able to notice how the rock is fragmenting, due to temperature variations between the minerals that make it up. On the surface, these are greater than those on the interior, resulting in the formation of thin sheets that progressively detach from it.

This process of weathering in rocks is known as thermoclasty.

11. Hillside Exposure

There are great differences in vegetation on either side of the creek. On the side opposite to us, sclerophyllous forest communities are predominant. On this side, we can find the thorn scrub.

The exposure of the hillsides regarding the movements of the sun can be sunny or shady. In our southern hemisphere, those facing north are more exposed to sunlight, heat and dryness, while those facing south, are shadier and colder.

The ravine bottoms, on the other hand, are shadier and more humid, allowing the formation of a more dense forest that is drawn linearly in its descent down the hillsides.

12. Clay Oven

Clay ovens are present in different sectors of the park, many of them are not visible since they are hidden by mud and plants that have grown over their debris. The ovens are a vestige of one of the main traditional economic activities of Central Chile: charcoal production. This activity dates back to colonial times and the process began with the extraction of firewood from sclerophyllous forest trees, preferably hawthorn, boldo, litre and peumo. The firewood was then introduced into the clay oven and burned in almost completely airtight conditions to make charcoal.

The ovens were built with layers of fresh clay arranged in a curved shape, a structure with small perforations all around it to allow the smoke to escape. The door used to be a piece of brass located at the bottom of the oven and was sealed with clay once the fire was lit.

Currently, because native tree species are subject to various threats, their use for charcoal production has been banned since their extraction and excessive logging have contributed to the loss of sclerophyllous forest area.

13. Chagual Shrub and Quisco

Now we alternate with another community of thorny scrub, where succulents such as Chagual (Puya chilensis) and Quisco (Leucostele chiloensis) predominate, sharing their space with a well-diversified shrub layer.

At the end of the 18th century, Abbé Juan Ignacio Molina described for the first time the puya, a name of Mapuche origin, as a South American genus. The chagual species lives only in central Chile on the slopes of coastal hills, in the coastal mountain range. It does not grow in the Andes Mountains.

Its leaves form large clusters and have strong thorns on their edges. A powerful stem is born from the center, and culminates in a grouping of many flowers, which are visited by hummingbirds and insects. It flowers in spring from September to November, although it does not flower when the previous winter has been dry.

This plant is used for reproduction by the chagual butterfly, the largest butterfly in Chile. It lays its eggs in its base and its offspring live as caterpillars between one or two years before their metamorphosis takes place.

The quisco grows in a tree form, like a branched chandelier, up to 8 meters high. It stands out for its thick, juicy and thorny stem, its large white funnel-shaped flowers and its fruits similar to the prickly pear. Endemic to Chile, it can be found between the regions of Atacama and Maule.

Some specimens of Chilean palm are also present here, as well as in the just visited forest communities, which demonstrates a great versatility to adapt to different environmental requirements and vegetational associations.

14. Cup Stone

The origin of these vestiges of human activity is not clear.

According to the Council of National Monuments "The cup stones are archaeological remains characteristic of the central zone of Chile, which would have been elaborated by hunter-gatherer peoples more than 10,000 years ago. Although they come in a variety of sizes and shapes, they are generally a flat, horizontal rock surface, in which shallow concavities have been carved in a circular or oblong shape. In general, they are located in spaces associated with ritual use, although it is estimated that they would have been used primarily for grinding seeds.”.

These early communities of the Llolleo cultural complex, hunters of fauna, but making vegetables a fundamental part of their diet, lived in small groups in ravines and valleys near water. They used their hands along with grinding stones and other drilled stones. They buried their dead around their houses and wrapped their children in clay urns, accompanied by objects.